The Bridge Mill

Recorded history

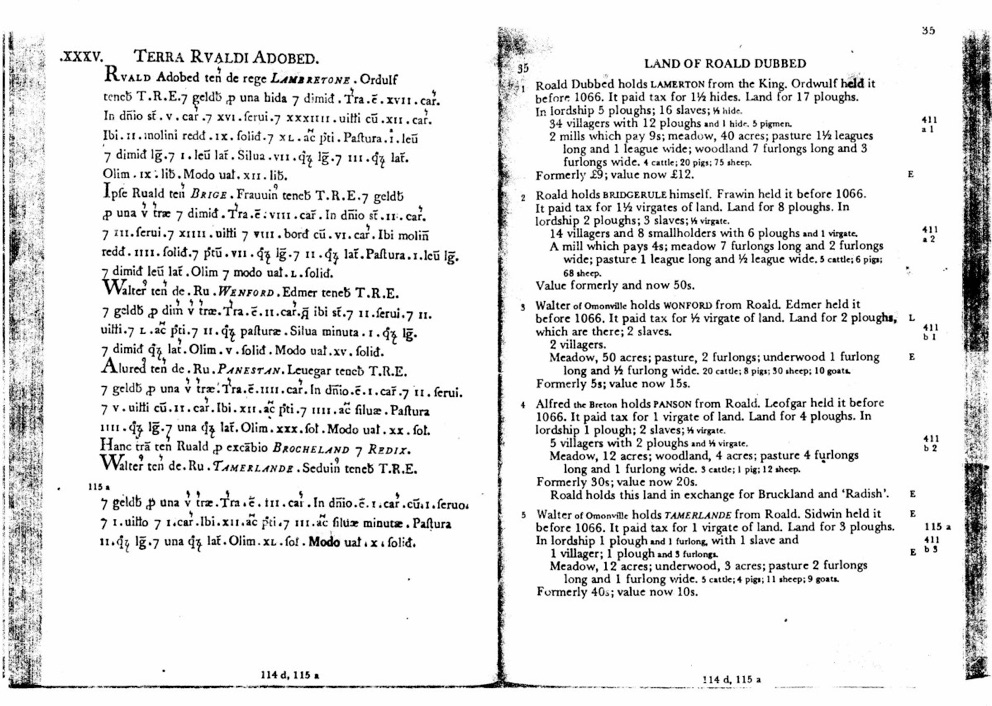

A charter of AD 762 contains the earliest documented reference to a watermill in England (at Cert near Dover). By the time of the Norman invasion watermills were in widespread use over much of the country and the Domesday survey of 1086 lists over 5000 of these. There were however surprisingly few in Devon, and most of these lay in the east of the county. West of the river Exe only 18 mills are recorded for the remainder of Devon, and only 6 for the whole of Cornwall. This is remarkable in a region so rich in flowing water, suggesting that the technology of water milling was spreading across England from east to west, and was only just starting to penetrate the southwest peninsular at that time.

On the river Tamar, only 4 mills were recorded by Domesday; one of these was at Brige (now Bridgerule) – “a mill which pays 4 shillings”. Frawin (the Saxon lord) held the manor before 1066, but it passed to the Norman knight Roald along with other local manors in return for his part in the conquest. These then are the first recorded owners of Bridgerule Mill.

See second paragraph for details of Bridgerule:

It is not uncommon for a Domesday site to remain in continuous use for milling right through to the twentieth century. A carefully chosen site had the best position available in the locality, and throughout most of the intervening centuries the 'soke rights' required all corn grown in the manor to be ground at the manorial mill, thus preventing competition. So it is fairly certain that waterpower has ground corn here on this site for more than 900 years. Naturally the buildings and machinery would have decayed and been replaced a number of times throughout that period.

The parish of Brige became known as Bridgeroald after its Norman lord, then by corruption through Bridgeruell and other variants to Bridgerule by the time of Risdon's survey of Devon around 1640 “where the Tamer's stream is so sturdy as it cannot be passed without a bridge, which was the original of the primitive name of this place”. The river then formed the boundary between Devon and Cornwall, and Polwhele records in 1797 a bridge ”each county repairing one arch”, so the river at that time must have been a more substantial watercourse then we see today.

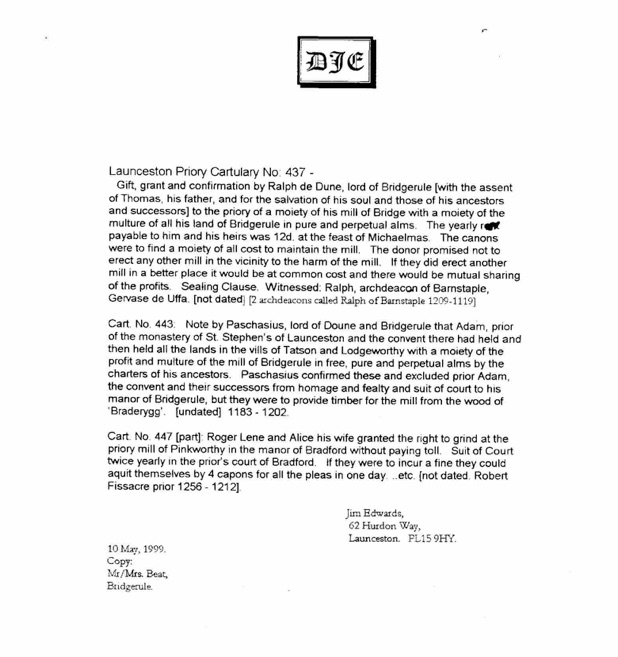

After the Domesday survey of 1086, the next documented reference to Bridgerule Mill is to be found in the records of Launceston Priory. We are grateful to Jim Edwards of Launceston for the original research that uncovered this information.

Cartulary no. 437 refers to a gift, grant and confirmation by Ralph de Dune, lord of Bridgerule to the Priory “with the assent of Thomas, his father, and for the salvation of his soul and those of his ancestors and successors” of a moiety of his mill (a moiety was a part, commonly a half-share). The canons were to find a moiety of all costs to maintain the mill. The donor promised not to erect any other mill in the vicinity to the harm of the mill. If they did erect another mill in a better place it would be at common cost and there would be mutual sharing of the profits. The document is witnessed by Ralph, archdeacon of Barnstaple; it is undated, but an archdeacon of that name held office from 1119.

Cartulary no. 443 contains a note by Paschasius, Lord of Doune and Bridgerule confirming that Adam, prior of the monastery of St Stephens of Launceston and the convent there, had held and continued to hold “a moiety of the profit and multure” of the mill of Bridgerule “in free, pure and perpetual alms” by the charters of his ancestors (multure was the toll paid for grinding, usually one sixteenth part of the resulting meal or flour). Adam and his successors were excluded from “homage and fealty and suit of court” to his manor of Bridgerule, but they were bound to provide timber for the mill. Again the document is undated but it falls within the period 1183 – 1202.

************************************************************************************************

After this, little detail is known until the late eighteenth century. At that time the mill and much of Bridgerule parish belonged to the Molesworth family of Pencarrow, Cornwall, and it remained as part of the Molesworth estate until 1920, when the Bridgerule lands were sold to pay death duties.

Throughout most of the mill's long history, then, the miller was a tenant of the controlling landowner. The Land Tax returns of 1780 onwards give the names of these tenant millers:

1780 - 1795 John Goodman

1796 - 1797 Thomas Goodman

1798 (no entry)

1799 - 1822 John Goodman

1823 - 1827 John Brimacombe

1828 - 1832 John Rogers

In some of those years John Goodman was one of two Assessors appointed to collect the tax within the parish, so he must have been a man of some standing within the community.

The Tithe Map of 1842 shows the layout of mill, watercourses and field boundaries much as they are today; the Tithe Apportionment of that date records the same John Rogers as tenant of the Mill house together with 6 acres of land.

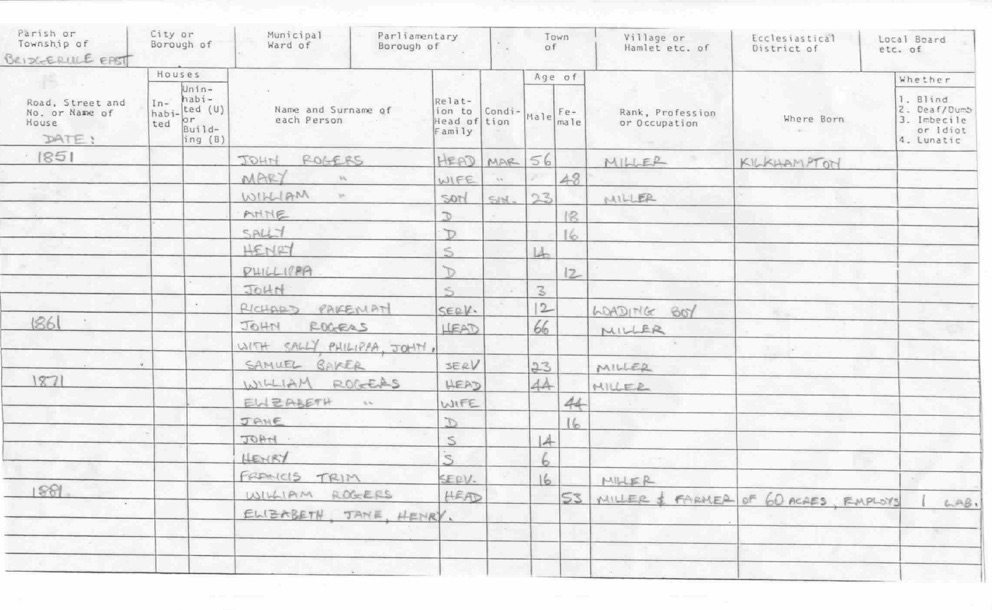

The census of 1851 tells us a little more about him. He was then 56 years old, married to Mary, 48, with 6 children ranging from 3 to 23 years old. Both he and his eldest son William are recorded as millers while a 12-year-old servant, Richard Pakeman, is a “loading boy”. This implies a thriving family business.

The Rogers family remained as tenants through three generations. William had succeeded his father by 1871, living here with his wife, 3 children and a 16-year-old servant, Francis Trim. The present mill was constructed around this time to replace an earlier building. The stonemason was William Vinnicombe, a local craftsman responsible for some other notable buildings within the parish such as the school and part of the rectory (now Glebe House). The stone used may have come from the nearby quarry below Churchtown hill and adjacent to the Bridge Mill land.

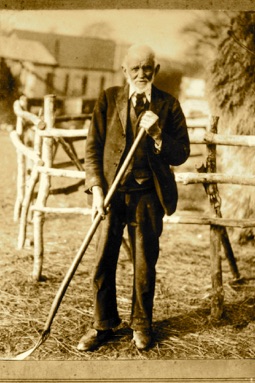

William Vinnicombe at 90 years old

Bridgerule’s “Grand Old Man” ( from the local paper at that time)

The 1871 census records William Rogers at 53 years old as “miller and farmer of 60 acres, employs 1 labourer”. His youngest son Henry took over as miller around 1889, and was still listed in Kelly's directory of 1897 as “Henry Rogers, miller (water)”, but by the turn of the century the long tenancy of the Rogers family had come to an end.

Fred Brock took over the tenancy and continued as miller until his death in 1918, when his son Francis succeeded him for the two remaining years before the mill was sold in 1920. By this time the Brocks were renting about 100 acres of farmland from the Molesworth estate plus additional land from neighbouring farms, so clearly the milling business had gradually declined and been supplemented by farming to an increasing degree.

The Brock family is still represented in the village today.

This pattern of decline was typical of watermills around this period in their history. Cheap imports of grain from the USA arrived in increasing quantities from 1870 onwards; these were hard winter wheats, difficult to grind finely between stones but well suited to the steel roller mills which were being introduced around the same time; the resulting finer, whiter flour became very popular, very quickly. Large roller mills were built at the dockside to process the imported grain, producing flour that old-established inland mills struggled to compete against. Many converted to grinding grist (animal feed) alongside flour to survive, then developed into grist-only mills, to finally close as uneconomic in the early part of the twentieth century.

Bridgerule Mill was finally sold into private ownership in 1920 along with 16 acres of land for the sum of £1,200. The purchaser was John Honey, a man whose roots in this parish could be traced back for at least three centuries. The parish register records for 21st July1660 a son born to Samuel and Mary Honey, and throughout the intervening years the surname appears time and again on documents relating to the village. The family is still well represented here today, so John Honey was truly a local man.

John Honey’s father - “Granfer”

The leat required a good deal of cleaning out and maintenance to keep the water flowing through from the river to the mill; no doubt this was a major factor in John Honey's decision around 1947 to abandon the use of water power. A 3~phase electric motor was installed to power the mill through a flat belt drive, but in 1952 John suffered a serious accident with this belt, losing one leg as a result. Disabled and growing older, he was persuaded to sell the water wheels and some of the internal drive gear for scrap around 1955. He died in 1959.

An old postcard of “Honey’s Mill, Bridgerule”

For several more years, relatives of John Honey worked the mill occasionally to grind their own grain, using a tractor with flat belt drive through the open doorway of the workshop. This finally came to an end in 1968. The Mill remained in the ownership of the Honey family until we came here in 1987.